19 July 2021

If enough of us ever get vaccinated to get over the immediate emergency, it will be useful to take time to reflect on the medium-term implications of the global pandemic for the governance of Australia and the world. There is much to be done and much we can learn.

The pandemic has thrown new light on the benefits and costs of globalisation.

The economic status of Australia and the well-being of its citizens are closely tied to aspects of globalisation. Australia is a relatively small economy with limited domestic demand. The nation has prospered through having natural resources in abundance which, given a worldwide free trade regime, can be sold to countries less well endowed.

However, the pandemic has woken Australia to the risks of too great a dependence on globalisation. It is now clear that the single most serious issue for the nation was supply of vaccine. In preparing for vaccination, the Federal Government made errors in commissioning and negotiating supply from other nations. This was compounded by decisions made by some of those other nations which were in their own interests and over which Australia had no control.

The problems posed by the absence of sovereign capacity to manufacture goods and services that become essential when the world faces a widespread emergency were apparent even before vaccination started. There were shortages of items of personal protective equipment and hand washing gel (in the days before we understood that soap and water was best). These were mitigated to some extent by the flexibility of some manufacturers who re-tooled rapidly; and by home-grown household activity, such as mask-making.

Incidentally, perhaps it would be wise to include toilet paper as a bottom-line commodity in forthcoming trade agreements that Australia signs.

On the other side of the globalism ledger, the pandemic led very rapidly to the effective closure of two of Australia’s major export sectors and employers: international tourism and international education. This was caused by interruption of another key element of globalism: the free and untrammelled movement of people around the world.

Fortunately, the export of natural resources, particularly iron ore and coal, as well as agricultural produce, seems to have proceeded unabated. The astonishing increase in the international price for iron ore, not related to the pandemic, has done much to shelter Australia from the worst economic effects of Covid-19.

Building manufacturing capacity and finding ways to make existing industries more resilient will have beneficial economic effects. Just as the shift to renewable energy sources is making new industries economic, so will national re-tooling for greater emergency self-sufficiency help to build Australia’s economy and provide employment opportunities.

Moves to mitigate against inadequate supply of goods and services needed in an emergency, and in response to the decline of major industries, provide incentives for Australia to rebuild its manufacturing sector.

In the 1960s manufacturing provided one quarter of GDP. By 2010 this had fallen to 6%, providing 8.6% of employment. In 2020 it was 4.2% of GDP and 7% of employment – or 853,000 people.

The Federal Government has indicated that it has plans for what it calls A Sovereign Manufacturing Capability Plan. It will apparently cover business opportunities both small and large, from manufacturing for niche markets right through to the production of guided weapons.

International agencies

As a middle-sized nation which benefits from both international trade and the rule of law, Australia has traditionally been a strong supporter of the bastions of globalism: multilateralism and international agencies. Once the health emergency is over it will be useful to scrutinise the performance of these agencies and to act on lessons learned about their structure, operation and value.

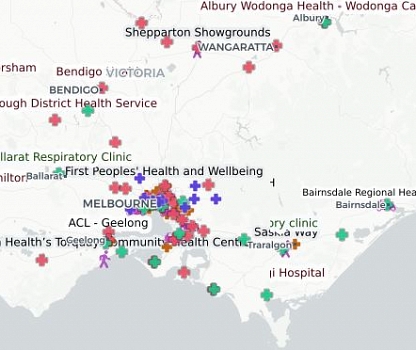

The agency most closely involved in the pandemic has obviously been the World Health Organisation (WHO). The majority view seems to be that the WHO had a poor start due to being slow in declaring the novel coronavirus outbreak ‘A public health emergency of international concern’, its highest level of alarm. Some commentators have attributed this to sensitivity about China’s potential reaction to such a declaration.

Since then, the WHO has been a critical and positive contributor to management of the pandemic. The challenge for the WHO was all the greater given that it was confronted by active opposition from the United States under Donald Trump. He cut funding for the WHO in May 2020.

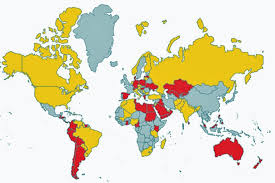

Some of the WHO’s most important work is concerned with global vaccine equity and the gap between richer and poorer nations – the so-called ‘two-track pandemic’. The scale of this challenge is illustrated by the fact that several affluent countries are already discussing the rollout of booster shots to their populations, while the majority of people in developing countries—even front-line health workers— have still not received their first shot.

This is a matter that needs urgent international agreement and action, in which Australia, as an affluent country, should take an active part. There is much to be done in the medium term to make the world a fairer place before the next pandemic or similar crisis emerges.

The most critical immediate task in world health is to ensure that developing nations are given all necessary support for obtaining and using vaccines. Supply in sufficient quantities is the core challenge and spreading it fairly between richer and poorer nations. One way to achieve this would be to assist medium-sized countries to establish the capacity for producing vaccines. Cost is a key factor and it is to be hoped that ways can be found for the sort of generosity shown by governments and the private sector over the last 18 months to continue to be demonstrated.

Given the massive impact on world trade and damage to the budgets of all countries, including those that are affluent that have been donors of international aid, the impact of the Covid-19 emergency on the people and governments of poorer countries may yet become unmanageable. Much will depend on the role played by international aid and trade in the new order.

One particular example of successful collaborative international action is COVAX. Its aim is to accelerate the development and manufacture of Covid-19 vaccines, and to guarantee fair and equitable access for every country in the world. Among other things it is working to ensure that donations of vaccine to developing countries are synchronized with national vaccine deployment plans.

Apart from the WHO, international agencies concerned with the pandemic include the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the World Bank and the OECD.

The IMF is preparing a Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation to boost the financial reserves and liquidity of its members.

The WTO is involved because cooperation on trade is needed to ensure free cross-border flows and increasing supplies of raw materials and finished vaccines. It is working on negotiations towards a solution around intellectual property, which remains the main sticking point in relation to making medications available at low prices. The WTO is also working on freeing up supply chains for vaccines and other medicines.

The World Bank has provided a $12 million financing facility for vaccination and has vaccine projects in some 50 countries.

In anticipation of an end to the immediate Covid crisis, preparations can begin for evaluation of the way international agencies have performed since the beginning of 2020.

Note: a modified version of this piece was published as Part 1 of Preparing for an evaluation of Australia’s response to the Covid-19, 13 July 2021.