1 Sept 2021

In two weeks’ time, as part of their employment arrangements, all staff of residential aged care facilities will be required to have had at least one coronavirus vaccination. That’s around 150,000 people in over 2,600 facilities.

There are two chances that this target will be met – one of which is Buckley’s.

Note: this is the second of three posts that have been delayed as I tried unsuccessfully to have them published elsewhere.

A sad, brief history

The Government’s national vaccine rollout strategy was released in early January 2021. The target population (c.20 million) was all of those 18 and over.

The highest priority (‘1a’) was allocated to quarantine and border workers, front-line health officials, aged and disability care workers, and aged and disability care residents.

On 1 February the Prime Minister said he expected to “offer all Australians the opportunity to be vaccinated by October of this year”. Later he said 4 million would be vaccinated by the end of March.

On 2 July National Cabinet agreed to adopt the “strong advice” from the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) to make vaccination against covid mandatory for all staff of residential aged care facilities.

This action will be underwritten by a grant program to help the centres and, through them, their individual staff members. Eligible payments will help with travel to the nearest vaccination site and cover for lost wages. The Federal Government will oversee compliance – which does not inspire great confidence.

What went wrong

Many things can explain what has gone wrong. In particular they include the shortage of vaccine supply, generalised incompetence and lack of urgency, an ill-disciplined approach to setting priorities for vaccinations, a curious absence of public information, and the usual confusion or overlap between federal and state jurisdictions.

Supply

Nothing has been more significant than the fact that, from the beginning, there has been an overall shortage of vaccine supply. This has cast a dark shadow over all aspects of the vaccination program. The shadow remains despite the arrival of Spring.

The government failed to make sufficient contractual arrangements to meet its commitment to have Australians at the front of the queue for vaccine. This was compounded by the failure of leaders, experts and commentators to ‘make real’ the different probabilities of sickness from coronavirus as distinct from blood clots.

An ill-disciplined approach to setting priorities for vaccination

Agreement on the priorities for allocation of vaccine, and action on them, will be critical for as long as there is a shortage of vaccine supply. Public debate on the matter has been impossible because most of the planning and management has been done secretly.

A sad and surprising feature of the response to the covid pandemic has been the failure to assemble, analyse and utilise data on all aspects of the phenomenon and to keep the public informed. There is so much the public (and, apparently, researchers) don’t know about a disease that threatens everyone.

Setting and acting on agreed priorities should have been a matter of the most importance. But unfortunately, as a nation, Australia has had a superficial approach to the matter.

Initially this could perhaps be attributed to disinterest or complacency. With very little covid around, the main criterion for setting the priority for a particular group of people was the extent to which they were vulnerable to serious illness and, potentially, to death. No one could object to the residents of aged care facilities being a top priority and, through them, the workers who care for them. In the unlikely event that the virus did appear it was the elderly who would be most vulnerable to serious illness and death. And society owed a debt of gratitude to the grandparent generation.

The wisdom of making aged care staff one of the highest priorities had been tragically illustrated by the second wave in Victoria. Of the 730 covid-related deaths in that State in the period from early July to late October 2020, 655 were of patients in residential aged care.

With the Delta variant rampant the competition for scarce vaccine has become even stronger. Given the second wave in Sydney and the rest of NSW, the balance between the potential criteria for prioritisation has shifted. It is no longer universally agreed that ‘vulnerability’ is the key criterion. Vaccination is now a key asset in the battle to limit the number of infections.

The new key criteria for allocation include geographical and demographic characteristics. Where you live and what contribution you are likely to make to spread of the disease have become as important as the extent to which your health is likely to be severely affected by the condition.

With the narrative changing from the suppression of cases to ‘living with covid’, the main purpose of vaccination will to some extent switch back and once again be to minimise illness and death.

A lack of public information

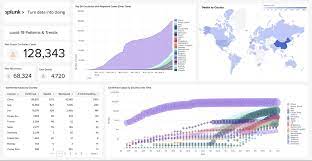

Surprising though it may seem in a country that has generally been well-served by agencies that collect and use quantitative information, the absence of data and public information on many aspects of the pandemic has been an ongoing problem.

Despite the fact that the aged care workforce had been a top priority since January, in the first week of June the responsible Federal Ministers, Greg Hunt and Richard Colbeck, admitted that they were not able to say what number of aged care staff had received zero, 1 and 2 covid vaccinations. Greg Hunt, Minister for Health, apologised to Parliament for an incorrect report on the matter. He confirmed in early June that 20 aged care facilities had not yet been visited as part of the national vaccination rollout.

It was a problem that, unlike the situation with vaccinations they previously required, the status of staff with respect to covid inoculation was not linked to payroll. Furthermore, it was not until June 2021 that operators were required to report each week to the Federal Health Department on the covid immunisation status of their staff.

Matching supply with priorities

Details of the schedule for receipt of vaccine supply must be matched against the priorities determined and thus the number of people who are eligible and who expect to be able to get vaccinated.

There is a State-by-State schedule of ‘allocation horizons’ but it is impossible for outsiders to understand. (https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/covid-19-vaccination-covid-vaccination-allocations-horizons)

This might be because the Federal Government itself cannot be sure of how much will be delivered from overseas or when. In Parliament this week the Prime Minister claimed that the speed at which vaccinations are now occurring has made up for the 4-month delay. He has even suggested that the rollout is going so well that the original target will be met by Christmas “or even sooner”. He credited this turnaround to the fact that the government has “been able to bring forward doses” and “has been able to achieve and realise additional supplies”.

In the same Question Time reply he said “We have more irons in the fire that will see further doses being made available”. [These are quotes taken verbatim from the PM’s QT speech. Some changes have been made to the Hansard record between ‘Proof’ and Final.]

All this is terribly imprecise. The uncertainty about how much is being received and where it is was illustrated by the on-again, off-again switching of some supply to Sydney’s worst affected suburbs. Just this week there seems to be the same uncertainty about special deliveries set aside for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Hopefully what is happening is that a detailed schedule for supply of Pfizer and Moderna is cross-checked against the planned rollout, which must be subject to agreed priorities. The next population groups to be eligible are the 16-39 year olds (from this week) and 12-15 year olds from 13 September.

It will be vital that these people do not face the same frustrations and logistical difficulties that many older people have already experienced. If the supply schedule suggests that there will be inadequate doses for aged and disability care, for all hospital staff (now very clearly a top priority), special rollout to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, year 12 students, selected hot-spots et cetera et cetera then the expectations of these other cohorts should not be raised.

The current situation

In Question Time this week the Prime Minister reported that double-dosed vaccination rates in aged care facilities is “upwards of 80%”. He seemed to regard this as a success, despite the long history of the issue, and attributed it to the priority he has given to vaccinations in aged care “which has enabled us to visit all of these facilities to ensure that the double doses are done”. It is not clear what “upwards of 80%” means, or how many of the other 20% have had their first.

The public now has a better appreciation of the uncertain nature of statements such as these. It needs to be clear, for instance, whether they refer to adults only and whether they mean the first jab or full inoculation.

The next key target for aged care staff is mandatory vaccination, to begin on 17 September. Every effort must be made to complete the task on time with a high level of competence and effectiveness.

Let’s get on board with Buckley. They’re all we have.

Note: this is the second of three posts that have been delayed as I tried unsuccessfully to have them published elsewhere.