At the beginning of the Second World War, Ted and his family lived in a small house near the Fremantle docks.

The dock area was resumed for military and security purposes. This affected so many families that the education system could only cope by switching to half-day schooling. You went to school from 9.00 to 12.00 or from 12.00 to 3.00.

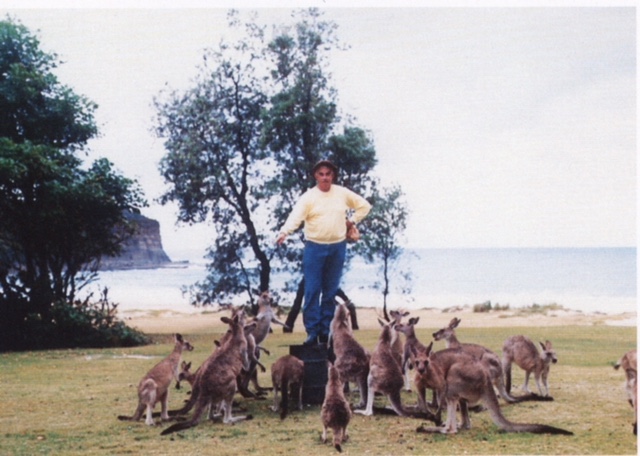

After a number of false starts Ted’s family moved to Spearwood, a market gardening and fruit growing area on the outskirts of Fremantle. In 1940, when Ted was 11, the family moved to Safety Bay, then a small fishing village some 20 miles south of Fremantle. Ted soon realised that for an adventurous teenager Safety Bay was about as good as it gets.

There was just a two-teacher school and Ted can still recall how happy he was there. The Headmaster was a great teacher, as was the second staff member. Both of them looked after three school years. Ted remembers the inspiration they provided. They used to bring all six classes together on Friday afternoons for a reading. Ted still remembers King Solomon’s Mines from this experience.

When not at school Ted and his friends were fishing, paddle boating, swimming and exploring their home areas and the small islands nearby. This included Penguin Island with its colony of Little Penguins, and Seal Island. One of Ted’s friends suggested they climb to the top of a nearby island – just a large rock used by birds as a nesting area. One day they climbed all the way up the steep sides to discover that the rock was cluttered with thousands of birds and covered all over with years and years of their droppings.

The two potential young entrepreneurs considered returning to bag up some of the droppings for sale to local gardeners. However when faced with its weighty logistical challenges this venture proved too challenging.

Ted would occasionally work on board one or other of the local fishing boats. These were 18 to 20 foot vessels, “little more than oversized dinghies”. They had a flat area aft for storing and handling the rope and the net.

Ted’s job was to help to retrieve the rope and net prior to its re-deployment. This involved getting very wet! To have a ‘lad’ for this work meant that at least one of the adult crew members could stay dry for the duration of the trip.

Net fishing at Safety Bay was a team pursuit, with two team members being on the beach and working towards each other, pulling the net to a close. This created an open channel for the entrapped fish to move into, at the end of which was the ‘pocket’, being a reinforced holding net.

It was to be hoped that there were not too many crabs in the catch because of the frenzied damage they would do to the fish in the pocket.

Ted was rewarded for this work with a feed of fish to take home to his mother.

Following his brief career as a deck hand, Ted started an apprenticeship in

patisserie. He stayed with his Aunty Thelma,trying to sleep during the day ready to be at work at 2-00am. He had to walk for about 40 minutes to sign on – there being no night-time public transport. After work Ted walked into town to catch a tram to his aunty’s house.

One night as he was waiting for the other workers and the boss there was a fight nearby which resulted in the death of one of the men involved. Together with the transport difficulties and a lack of sleep, this alarming experience proved too much. Ted left after about three months.

His big break came with a job in Fremantle in 1944.

Given that the world was at war, he was surprised to find that GJ Coles was still importing pottery, china and kitchenware from England. In Fremantle there was a team responsible for unpacking the large cane baskets of crockery and homeware recently arrived from the UK.

The Manageress was Miss C.

.. Her team comprised ‘Mister Mac’, Miss M. and Ted. Mr Mac and Ted handled the actual unpacking. Frequently the packaging was wet straw, which meant that cleaning was needed before Miss C. could finalise orders to be filled for distribution to various Coles stores in Western Australia.

Ted was a tall 15 year old, whose dress was always short pants. Miss C. insisted he be fixed up with long pants and it has always been Ted’s suspicion that Miss C. paid for the first pair herself.

On his first day in the new job, Mr Mac told Ted that Miss C. wanted to see him at lunchtime. Ted went ‘upstairs’ to find that his three colleagues had made up a plate of lunch for him from their own provisions.

Maureen was ‘upstairs’ and did the stock-taking. Ted enjoyed stocktaking because of the opportunity to have the company of another young person.

It was Mr Mac who explained to Ted that having been to the toilet it was essential to wash one’s hands. And it was Mr Mac who explained to Ted about the importance of brushing one’s teeth. In 1944 Ted and many others like him had no toothbrush and little conception of oral hygiene.

During his time at GJ Coles Ted took the bus to and from Safety Bay each day for work. The bus fare was ten shillings a week, leaving nine shillings a week for his mother.

One day Ted was absent from work, having heard at lunchtime that the war was ended. He made his way to the docks – already re-opened – and helped the crew of a vessel there obtain fresh oranges from town.

Not long after this Ted saw an advertisement encouraging 16-year-olds to join the Navy as cadets. He resigned from Coles and made application but was unsuccessful. He was therefore out of work.

However, Ted was soon on his feet again. One of his friends at Safety Bay was the daughter of the owner of the Savoy Hotel in Perth. Ted became the hotel’s Junior Hall Porter. His main responsibility was running messages between various hotels in Perth. He had no bicycle – just shanks’ pony.

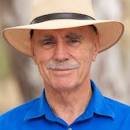

When he recalls his upbringing in Western Australia and his transition from knockabout kid to member of a workforce team, Ted reflects gratefully on the welcome he had and the help he was given by the likes of Miss C., Maureen and Mr Mac. One of Mr Mac’s specific instructions to Ted was to read Dale Carnegie’s book on self-improvement. Which he did.

Eighty years on, let us reflect on and give thanks to the three of them for the decent, kind and caring workplace they provided for a young person just setting out on a working life.

Their generosity has never been forgotten by the young man who went on to have a distinguished career in the Royal Australian Air Force. How he got there is a story for another day.