This is the second piece I have written about quad bikes for this blogg. The first (Quad bike safety, 20 July 2016; in the Rural health section) gives background information about the issue and makes the case for a ‘mixed mode’ response to quad bike accidents and fatalities:

” – it is not sensible to rely only on technical or engineering fixes. It’s also about behaviour and attitudes to risk. Many organisations – – are urging farmers to attend training courses about safe riding, following manufacturers’ instructions”.

For that first piece a couple of practising farmer friends contributed thoughts about some of the realities of the (proper) agricultural use of all terrain vehicles – and about some of the non-farm reasons for accidents:

- the effect of mandatory wearing of helmets on attitudes to risk;

- the impracticability of banning children from riding them; and

- the particular risks associated with visitors to the property.

Accidents are still occurring, some of them fatal, so the question of how much regulation is the right amount remains an issue. Somewhere on the spectrum between anarchy and ‘A Nanny State’ is the right spot for dealing with the matter.

This second piece provides a little more history, evidence of how reactive and ad hoc the approach to regulation currently is, and some links to further information.

The Mount Isa Statement

The 6th biennial Are You Remotely Interested? Remote Health Conference, held in Mount Isa in August 2012 incorporated Farmsafe Australia’s Conference. One of the outcomes was the Mount Isa Statement on Quad Bike Safety. (https://sydney.edu.au/medicine/aghealth/uploaded/Quad%20Bike/mtisa_statement.pdf)[1]

The Statement reports that fitting crush protection devices (CPDs) could reduce the number of quad bike deaths by up to 40 per cent. It asserts that the science underpinning the manufacturers’ opposition to such devices has been demonstrated to be invalid.

The Statement proposed that CPDs be mandated for all quad bikes, with technical standards for them having been developed. New sales of child size quad bikes should be stopped and children under the age of 16 should not be allowed to ride quad bikes of any size.

That was in August 2012. Two years later a report on progress with recommendations from the Mount Isa Statement, written by Richard Franklin, Sabina Knight and Tony Lower, was published in the on-line journal Rural and Remote Health. (www.rrh.org.au/publishedarticles/article_print_2687.pdf)

That journal article reiterated the immediate steps people can undertake to keep themselves and others safe when using a quad bike: initially selecting safer vehicles to use; fitting them with crush protection devices; not carrying passengers or overloading the quads; and wearing helmets.

In the next year, 2015, 15 people were killed while using quad bikes on Australian farms (http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/aghealth/publications/reports.php).

Ad hoc regulation and incentives

In May/June 2016 there were two fatal accidents in Victoria involving quad bikes. On the last day of National Farm Safety Week that year (22 July 2016; http://www.farmsafe.org.au) the Victorian Government announced that $6 million would be available to help farmers buy roll over protection bars for quad bikes. Farmers were able to access $600 per bike for fitting operational protection devices for a maximum of two rebates per farm business, or get a rebate of $1,200 towards the cost of buying a new vehicle with safety protection already installed.

The farm lobby welcomed the announcement and again argued that manufacturers should start providing roll bars on new quad bikes as standard. Manufacturing groups continued to argue that the money and effort would be better spent elsewhere, with helmets being the number one priority and rider training also important.

WorkSafe Victoria tightened the rules around quad bikes, requiring businesses to install roll-over protection devices on such vehicles used on a work site.

Typical compensation claims from an employee injured in the agriculture sector involve one and a half weeks off work. Overall, claims by employees in agriculture require longer periods off work than those in any other industry in Australia. (http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/SWA/about/Publications/Documents/759/Work-related-injuries-fatalities-farms.pdf)

The focus of National Farm Safety Week in 2016 was that safe farms are more profitable farms. One of the agencies promoting this message was the Primary Industries Health and Safety Partnership, which has produced and published some useful materials on the subject. (www.rirdc.gov.au/PIHSP)

On Sunday 5 March 2017 two people died in NSW as a result of quad bike accidents: a 60-year-old man and a six-year-old girl.

On Thursday 9 March the NSW Government announced a doubling of the $500 rebate on the purchase of suitable helmets or safer side-by-side vehicles for riders.

To qualify for the rebates, farmers need to have completed an online course and attended a SafeWork NSW training day or met with an inspector.

In February 2017 the ABC reported that free quad bike safety courses run by SafeWork NSW and TAFE had been cancelled due to a lack of numbers. (http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-07/quad-bike-courses-cancelled-lack-of-interest-despite-deaths/8247216)

Quad bike riders in Queensland must now wear a helmet on public roads and are prohibited from carrying children under eight years old.

There is discussion about making motorcycle-type helmets compulsory when riding quad bikes on private property.

There is a wide range of views on the best way forward.

And everyone agrees on one thing:

“It will never happen to me.”

[1] all of the links in this piece were checked and accessed on 17 March 2017.

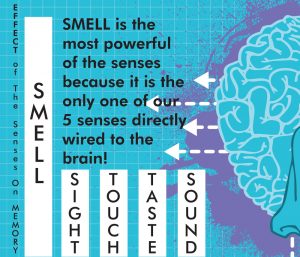

the mistake yourself of underestimating its potency. When you first arrive on site, and again immediately before you leave, be sure to spray the toilet and bathroom with an instantly recognisable cleaning agent. In a larger house, we recommend you use industrial strength agents. A good trick is to leave the extractor fans running in the kitchen and bathroom, which has two beneficial effects: first it spreads the cleaning odour throughout the house and, secondly, it requires the host to touch the off switch on these devices when they get home.

the mistake yourself of underestimating its potency. When you first arrive on site, and again immediately before you leave, be sure to spray the toilet and bathroom with an instantly recognisable cleaning agent. In a larger house, we recommend you use industrial strength agents. A good trick is to leave the extractor fans running in the kitchen and bathroom, which has two beneficial effects: first it spreads the cleaning odour throughout the house and, secondly, it requires the host to touch the off switch on these devices when they get home.